The following article was first published in April 2022 on a Methodist theology site. I wrote it less than a year before my eventual dismissal from the evangelical college that had employed me for well over half a decade.

I repost it here partly because I think others might find it helpful because the issues remain more “live” than many of us realised (and have been reiterated by Matt Walsh’s recent film, ‘Am I Racist?’, which featured one of the authors I mention in the original article).

I have also added an addendum at the end, reflecting on what I think has changed about how we think and talk about these issues even in such a relatively short amount of time.

Another reason to include the article here is because I’m not sure how long it will remain on their site undetected. It may eventually be seen as a crocodile hiding in the swamp in need of urgent “relocation” by not-so-well-meaning Methodists intent on purging their platforms of all they deem “unholy”.

I remember at the time of its publication the DEI officer for the Methodist Church got in touch with me with “concerns”. As I recall, we had an interesting theoretical conversation about the inherent contradictions in the Methodist conception of “inclusivity” as I saw them. These were contradictions of which I eventually felt the very real force when they were wielded against me less than a year later.

The article also featured several times as evidence in court for my tribunal earlier this year, having also been cited during my suspension and disciplinary process, with another high-up Methodist at the time having used it to accuse me of white supremacy. Let the reader decide…

It has become customary at theological conferences nowadays to include a panel discussion on race. These tend to revolve around the problem of “whiteness”, with the invariable outcome that the white people present should become, in one way or another, less racist. If we’re unsure whether we are in fact racist, we’re told it’s probably in there somewhere, covertly submerged within our very deepest theological convictions.

This intensity of focus is not difficult to understand given the parallel tensions within western society at present, exacerbated by the viral responses to the death of George Floyd, an event which seemed to take on cataclysmic significance, catalysing a new “great awakening” of racial consciousness. Many theologians and preachers even saw the phenomenon in divinely revelatory terms. Pulpits usually reticent to preach socio-political issues suddenly found their sermons saturated with Critical Race Theory alongside numerous apologies for white privilege.

The super-charged narrative means any theological panel discussion tends to become significantly less “discursive” than expected. In one recent panel I attended, an influential black theologian lamented the lack of BAME representation in UK theological institutions, stating this was, in no uncertain terms, “a demonic apartheid”. Thus, any white theologian within UK theology is necessarily a perpetrator of deeply oblivious systemic oppression, the kind Hannah Arendt called “radical evil” (think Eichmann et al!). How does one begin to respond to such claims within such a climate? The person making this comment then added that the time was over for yet another panel on race – radical action was the only solution left.

I’m certainly not unsympathetic to homiletical rhetoric on significant issues, nor to critiquing inconsequential virtue-signalling panels. Indeed, the academy often seems to specialize in prolonging debates precisely to avoid transformative action! But what if you don’t agree with the premises – let alone the conclusions – of the discussion? What if you do need to talk more? What if the idea that most-white-theologians-are-unknowingly-racist-especially-if-they-think-they’re-not is wrong? How could someone articulate such a belief without incurring the charge of “whitesplaining” (an always-pejorative term connoting an essentially undefendable accusation)?

It was Robin D’Angelo’s bestselling book, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard For White People To Talk About Racism (2018), where the astonishing claim was made that “rational argumentation” was a typical “behaviour” of white people when accused of racial privilege or bias. Charitably, this likely refers to the stacking-up of countless propositions purely to enhance one’s invulnerability to critique. But the obvious problem with D’Angelo’s observation is that only via some form of “rational argument” could we have any hope of being persuaded that such diversionary filibustering was even wrong. The notion that rational argumentation is an ethnically particular “mode” of engagement is an alarmingly racist claim with disturbing implications – yet robust discussion of such problems has become virtually impossible.

This problem echoes the ill-fated era of Unconscious Bias Training, eventually scrapped by the Civil Service after it was discovered that, far from reducing racial tensions and inequalities, it often made them worse. Meanwhile, churches who already came somewhat late to the systemic antiracism party continue to roll out such training in the vain hope it offers some pneumatological magic to heal deep-set wounds which fall within the purview of the Gospel alone. Whenever someone tentatively points this out – say, at a conference – the increasingly common response is that “the Gospel” is itself a “white” construction (thus, just the kind of thing a white person would invoke in general to avoid confronting racism in particular).

The Church rightly wrestles with its own problematic legacy on race, a problem still bearing wounds for many communities in today’s world. But Christian theologians and churches have too swiftly adopted strategies of racial reconciliation which not only find their basis beyond the Gospel, but often actively undermine it. The adoption of such strategies grates against much of what was revealed and achieved in the Cross and Resurrection (obvious examples include new birth, expiation of guilt, divine grace, and paradoxical forgiveness – there are many more!).

It’s not coincidental that just when academic theological conferences are hosting panels debating systemic whiteness, the very same debates were already occurring in other subjects (decolonising mathematics is the latest iteration). Regardless of reverse-engineered public statements, it’s clear that the principal lens through which much of the Church views race today is not the Gospel. Our theology must always remain attentive to the cries and laments of injustice in our world. But it’s concerning when the roots of such attentiveness are identical to what was already happening before the Church “caught up” with the appropriate rhetoric/paradigm/programme.

Tertullian’s famous warning of the irreconcilability of Jerusalem and Athens can often be overstated, but it should never be far from our minds today. True, the Church has always made use of non-Christian wisdom, but usually via annexation rather than wholesale adoption. We live at a time where western Christianity’s ingratiation in worldly systems of thought and action is epidemic. To even hear the declaration of “worldliness” today often brings patronising eye-rolls rather than honest Biblical self-reflections on the indistinctness of the Church’s prophetic witness.

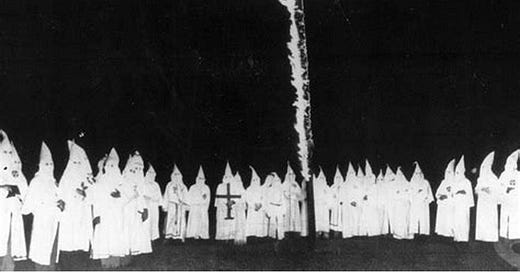

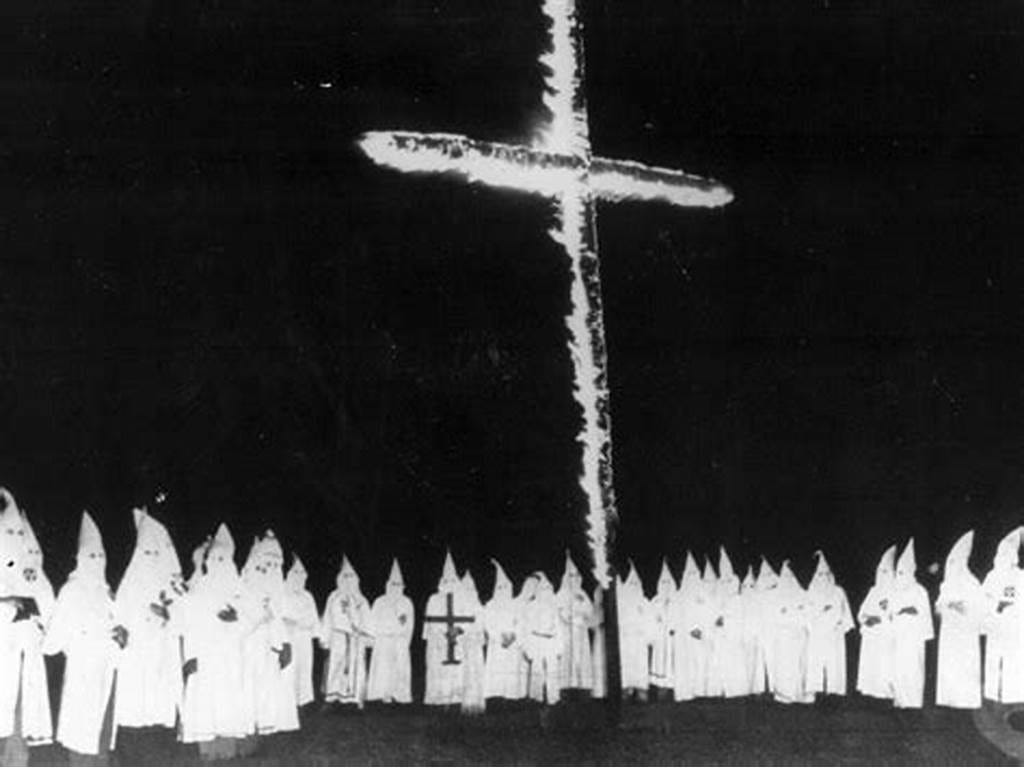

Ironically, the Church’s historic complicity with racism is rightly deemed heinous precisely because it was “worldly”, because it repudiated the logic of the Gospel. In our fretful attempts to confront this legacy today, we inadvertently allow a worldly ideology (“antiracism”) to become a gospel unto itself. We must allow the Gospel to interrupt us on its own terms, however inconvenient such terms may be at any given point. If not, the light that the Church alone is given for the sake of loving the world is hidden under a bushel for the sake of pleasing the world.

The above article was originally published at Theology Everywhere in April 2022

Addendum: The Climate Change on Racism

Reflecting back on this article now, in one sense it provides an insight into a world that has already changed rather drastically.

Many people now see these issues in a much clearer light than they did at that time. I am talking as though it’s decades ago but, as I write, it’s little over two and a half years ago! Such has been the drastic scale of change in the socio-political landscape in the West even in very recent months.

It feels as though we have been at war for the last several years. And we have, of course. Culture war is war, with real consequences in real time. Depending on the outcome (and the victors) its impact will lead to great damage and/or restoration within society over the long haul.

Whilst I have been on a trajectory of thinking about socio-political and cultural engagement issues since around 2015 (when I taught a course on the topic of religion and cultural crisis at the University of Aberdeen), it was only in 2021 that I decided to start coming out on wider online platforms to talk about “culture war” issues more specifically and consistently.

At that time, very few evangelicals were speaking out on such issues (especially not in the UK). Since that time the landscape has changed significantly (especially in the US) and I have observed more and more Christians willing to stand up and speak out for their beliefs, refusing to shrink back as has too often been the case in the recent past.

The cult of #Woke which exacerbated so many of the race-related issues in western society in recent years had been incubating in the depths of western institutions for many years before it came out in the open. This is why, despite signs of genuine optimism that its powers are waning, it will still take some time before #Woke truly dies out. Even so, we now face new challenges and new priorities in its aftermath.

If we do manage to push back the inherent racism of anti-white DEI tyranny successfully, we already know there will be a good deal of reactionary litter to clear up in the aftermath. One of these is the growth of what some have called the “Woke Right”. The premise here is that the same sense of idolatrous race identity we saw in the blackness > whiteness perspectives of #Woke are now being accommodated from the other side.

Disenfranchised white men, rather than feeling ashamed of their whiteness, are now rejoicing in it in ways most of them probably never would have done before being so comprehensively slandered as racists when this was not the case. Still reeling from this systemic targeting of whiteness, many now seek to explore whether it’s ok for them to care about their own “tribe” in ways that never occurred to them before they were so targeted.

At a time during which many are also rediscovering the importance of family and patriotism, it is understandable that a love and/or gratitude for one’s “own people” should not automatically necessitate hatred of those who are not one’s own people. As Chesterton said: how can you appreciate another man’s love for his country if you have not learned to love your own?

As we discussed in a recent Goodfight episode, the propensity to call Trump 2.0 a reinstitution of National Socialism shows the kind of ideological derangement that still exists. Christians too must reject the all-too-easy big level conflation of national patriotism with idolatrous racism whenever they see young men expressing long overdue gratitude in their heritage.

Technically, love of one’s nation or people need not have anything at all to do with the colour of one’s skin, of course. But it may seem as though it does sometimes, depending on the nation, and because so many westerners have been trained to see such issues through a pejoratively racial lens, as a further propellor for multicultural ideologies. The reverse reactions to the obvious problems of multiculturalism in the West, however, are now growing faster than many realised.

I appeared on a podcast last year where I was asked to prove that the Bible even sees racism as sinful, and where I was told that racial segregation in the US prior to the Civil Rights movement was actually a positive thing. I was also asked about immigration in the UK and was asked why we don’t simply get rid of the immigrants because Britain was a “white man’s country”. Perhaps the most bizarre aspect of this is that the host asking me all these questions was not white, but black! Quite simply, I did not have a frame of reference for these questions at the time. These are just not the kinds of conversations that even exist in the UK (at least not on platforms with almost 600,000 subscribers!).

More recently, there have been all sorts of controversies related to “White Boy Summer” and its less-than-subtle pro-fascist connotations, and the debates around the origins and ends of the “post-war consensus”. Such issues are, by various degrees of association, already causing battle lines to be drawn and causing numerous “brother wars” within Reformed evangelical circles. Christians otherwise very much on the same team viz-a-viz reclaiming the lordship of Christ against the “anti-racist” racism of the last decade, are now increasingly wary of Christian voices to their Further Right who—not content with merely refuting #Woke—have been catalysed to rethink much they have been told about the history (and future) of western people.

I won’t go into the details of all the particular controversies here other than to note that they demonstrate something of the very real challenge which lies ahead on race issues among Christians in the West. What were very recently only fringe ideas about which one might make hypothetical reductio ad absurdum arguments, have now moved to the front lines of Reformed evangelical discourse. The issues surfacing in our time—including their historical origins and their contemporary expressions—are more complex than they may at first seem; it will likely take some time before they are adequately unpicked, disentangled, or adequately resolved.

In the rapidly changing future of western culture which lies before us—into which, many of us are walking, running, writing, preaching, tweeting, and podcasting—it already feels difficult to keep up with so many paradigm shifts and cultural/missiological assumptions being called into question all at once. The Overton Window is moving, and we cannot afford to put our shields or our swords down on either side.

Our enemy is the father of lies, and he continues to prowl in the hopes of devouring our reception of the truth, wherever permitted. We will best defy our enemy by pursuing the truth in all things. As we do so, there is an urgent and ongoing need to remain not only curiously vigilant, but faithful, hopeful, and loving, however much reputational inconvenience the truth may cause, as it so often does.

"Reputational inconvenience" is the single reason leadership in well known missional organizations in the US refuse to repent of imposing DEI training on their missionaries. God's truth marches on without them. Unless they repent, a shameful, nameless 'death in the wilderness' awaits them. Those are very slow deaths and their reputations will die with them.