The Singability of Christianity

An Old School Hymnbook, a 1940s Diary, and the Singable Power of the Gospel

Why did so many children grow up singing Christian hymns in school assemblies? How is it that Christians so often seem to come with songs attached? Why has Christianity always been a “singable” thing?

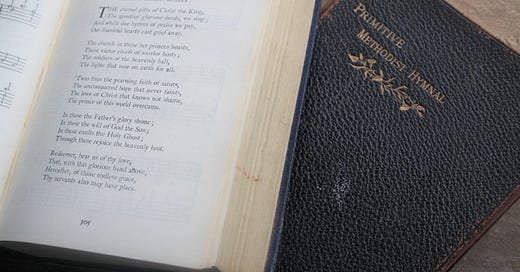

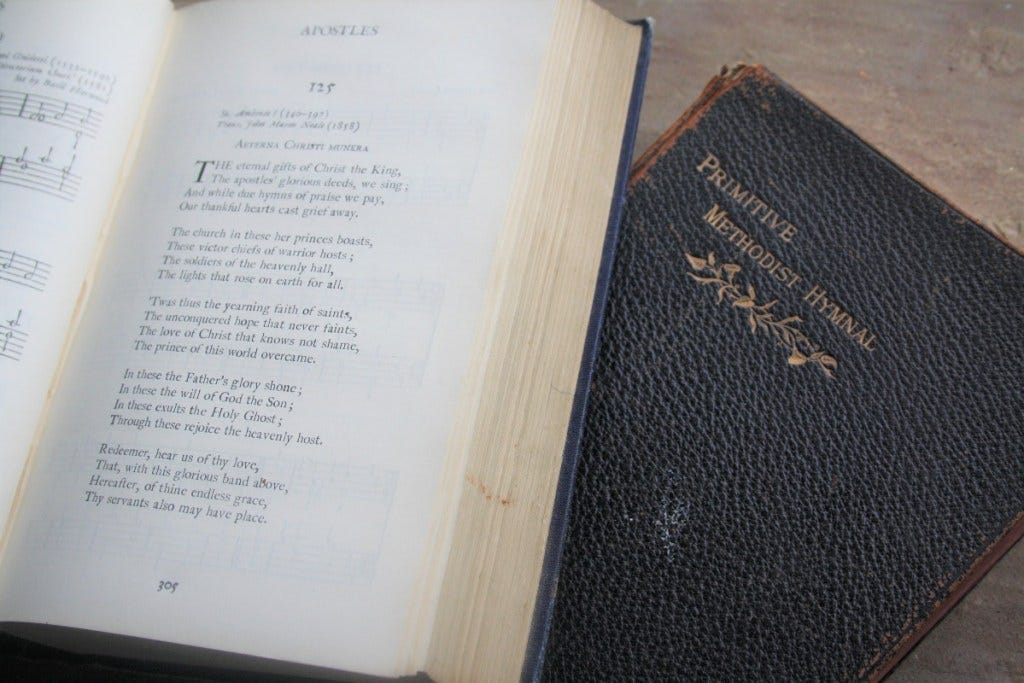

The Tale of a Hymnbook

In my first week at secondary school we were given our own little blue hymnbook. We were told to write our name on the inside cover, to bring it with us to all hymn practices and assemblies, and to keep it in respectable condition. We were told how we could do this by fitting them into the inside pockets of our school blazers. These pockets were, in fact, suspiciously hymn-book-shaped. It was as if the whole process had been designed to ward us off carrying around anything more exciting, dangerous and/or delicious.

Young boys, however, always seem to find a place to stow away such things. Hence, we often managed to wedge in various coins, football stickers, half-eaten chocolate bars, and inexplicable wads of receipts. I can only assume that we only kept such a volume of receipts so as to seem a little more grown-up, as if a day might come when we’d be required to provide a comprehensive account of all tuck shop purchases to a jury. In any case, those little blue hymnbooks sat there in those custom-tailored pockets like awkward paving slabs. You dug around them, not within them, to find treasure.

Over time, the pages of those hymnbooks inevitably became significantly less respectable. Upon teacherly inspection, however, you could always pretend their dog-eared state was down to pious overuse, as though in your spare time you really had been poring over the verses. Respectably or otherwise, these hymnbooks accompanied us throughout our entire school life. We sung from them (or pretended to) several times each week, year after year.

Most of us weren’t even remotely “Christian” as far as we could tell at the time. So we had little idea what any of what we were singing about actually meant. At breaktimes we’d occasionally mock-sing the more dramatic-sounding lines, like Jerusalem’s “bring me my bow of burning gold…” (a fitting prelude to a playground skirmish), or Guide Me O Thou Great Redeemer’s “feed me ’til I want no more!” (an ode to the lunch queue). Yet whatever state that we or our little hymnbooks were in, these strange words seemed to stay with us, however little we knew it.

Dreariness to Joy

Today I think back to such words very differently, conscious of all I missed out on by not caring about them at the time. Odd lines still return to me now and then, usually inspiring some fresh investigation into their origins. One such hymn was Lead Us, Heavenly Father, Lead Us (written in 1821 by the nineteenth century architect, James Edmeston).

My actual memories of singing that hymn weren’t particularly delightful. One especially gloomy line often came to mind: “lone and dreary, faint and weary / Through the desert thou didst go”. To this eleven year old, it seemed to capture as well as anything what it felt like to be at school on a cold, dark, damp January morning—the midwinter delights of Christmas long behind and the vigorous hope of Spring still far too far away.

Strangely enough, the 1986 editors of the New English Hymnal actually tried to get rid of that line in Edmeston’s hymn, attempting to swap it for something more generic. They “felt it desirable to abandon the description of our Lord as ‘lone and dreary’”. As much as my eleven year old self might have agreed with this marketing strategy, to do so would have been a grave mistake. Why? Because it’s important that we know that Christ did in fact face loneliness and dreariness.

Indeed, it is only because of Christ’s actual aloneness and dreariness that we have anything worth singing about at all. Jesus knows about cold, dark, damp January mornings. He knows not as a distant observer but as one who inhabited this earth, who “didst feel its keenest woe”, and who took it all with Him to the Cross.

As Edmeston’s last verse evokes, the Spirit who came down upon Jesus before the wilderness is the same Spirit who descends upon us today, flooding our hearts with cosmic joy, love, pleasure, and indestructible peace:

Spirit of our God, descending,

Fill our hearts with heavenly joy,

Love with every passion blending,

Pleasure that can never cloy:

Thus provided, pardoned, guided,

Nothing can our peace destroy.

Given the quite remarkable promises offered in such words, it ought to be a strange thing that so many schoolboys like me did not pay more attention to such words at the time. A lifetime of tuckshop receipts couldn’t come close to cataloguing the delights offered and sung about so freely in this gospel. Perhaps some of us are now so accustomed to repeating the Gospel that we no longer see it as all that delightful after all.

The reason Edmeston’s little hymn kept getting sung across generations of school assemblies because, like many hymns of its time, it speaks profound truth to the depths of the human condition. And such words keep speaking, even if it may sometimes take a while for them to sink in. The words to articulate that human condition might change between centuries but the condition itself does not. This remains the case even for those who consider themselves too clever for the naïveté of “religion”, or for those who have ever found themselves burnt out by it.

Who has not at some time or other felt the need of divine guidance “o’er the world’s tempestuous sea”? What honest person has not cried out to God (whoever they thought he might be) at their darkest (or finest) hours? There’s something about faithful songs of worship that have a way of getting at the longings of the human heart. It was the ardent singing of Moravian Christians in a storm-tossed ship that first convicted John Wesley of his true spiritual desperation and his own lack of Christian assurance by comparison when faced with a genuine crisis.

A College in Memoriam

When I worked at Cliff College (in the “Wesleyan” tradition) I used to love reading stories of lived faith from older eras of the college’s life, which often involved the power of singing and proclamation. In my time there were two delightful elderly archivists, Clive and Russ, who truly lived and breathed the heritage of the college. They were both in their eighties (or close to it) when I first arrived there almost a decade ago, having both been in/around the college in one way or another for well over half a century. One of them was even able to speak (in some detail!) of Billy Graham’s visit to the college in 1954.

These two men were like living relics of what that institution used to be and stand for. I think they knew that, having seen the college drift into what it ultimately became in the modern era, despite the efforts of many of us to see it return to the faithfulness and fertility of the soil in which it was first planted. Even from my very first day there, Clive and Russ used to put old pamphlets into my pigeon hole or under my office door (and I’m sure I was not the only recipient of this “bonus” postal service!).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to That Good Fight to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.