“What on earth are you doing in Iraq…?”

These next two posts may seem slightly different to the norm: part-travelogue and part-reflection on the complexities of religious “unity”. They are, in a sense, siblings to a piece I wrote last year after the International Religious Freedom Summit (IRFS) in Washington.

Iraq…

So: “What on earth are you doing in Iraq…?” It’s a fair question, one which a good many people asked when I told them I was going there. Although it’s been over twenty years since the second Gulf War, it takes a long time to think of a place beyond its “warzone” status, especially those of us who vividly remember watching the unusually detailed round-the-clock news coverage of the war on TV. It’s hard not to immediately picture tanks, deserts, dictators, and perpetually damaged buildings, when that’s basically the only cultural reference point you’ve ever had for such a place.

Depending on who you speak to, of course, I wasn’t even in “Iraq” at all; I was in “Kurdistan”. This is a geopolitical region covering areas of Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey, housing fifty million Kurdish people, yet having its own regional governments in each of these nations, and its own central government, which is based in Erbil in North-East Iraq, the very city I was visiting. The closest parallel I can think of is somewhere like Wales or Scotland within Britain; though I’m told that the closer parallel is somewhere like Basque in Spain, or Quebec in Canada.

None of this yet answers the initial question, of course: “What on earth were you doing in Iraq (and/or Kurdistan)…?!” Well, I was invited to the inaugural Kurdistan National Prayer Breakfast, of course. Weren’t you…? At first I was unsure this was even a real thing. Is it legitimate? Can you even have a “national” prayer breakfast when you are not yet internationally recognised as “a nation”? Well, apparently, you can. Or at least, no one seems to stop you if you do!

A Government Car

After a very cramped and uncomfortable night flight connecting from Istanbul—in which my seat’s headrest was treated as a walking stick by various large men walking up and down the aisles in perpetuity—I emerged from the plane onto the concourse dazed and sleepless, still not entirely sure whether the thing I was going to was a real event, nor that the country I was going to was a real country, nor that the men due to greet me at the airport would actually be there, given that it was 3 o’clock in the morning.

To my pleasant surprise, just a few steps later two men in suits were indeed standing there halfway along the concourse, with my name printed out on a piece of paper (slightly misspelt, but good enough given the circumstances!). I was then ushered through a door off the concourse down some steps and back onto the runway, where a luxury car was waiting for me. After a short journey the doors opened and a red carpet emerged taking us into a palatially spaced room where a waistcoated waiter was serving various complimentary drinks to the few people dotted around the room. I couldn’t afford to even buy a drink on the flight as even water was extortionately priced, so this immediate upturn of circumstances was an unexpected delight.

A small part of me still wondered if I had been taken here by mistake, but I certainly wasn’t going to correct anyone, not at this hour of the morning. Within ten minutes or so, the men returned with my passport stamped and sorted, and showed me to the car that was waiting to take me to my hotel. This kind of VIP treatment became fairly standard throughout the entire event. Although I had to cover my airfare, the event covered all transport and food whilst we were there, ferrying us around in Kurdistan governmental protocol security cars with darkened windows, even providing doctors on hand at each hotel, laden with piles of medication should we need it.

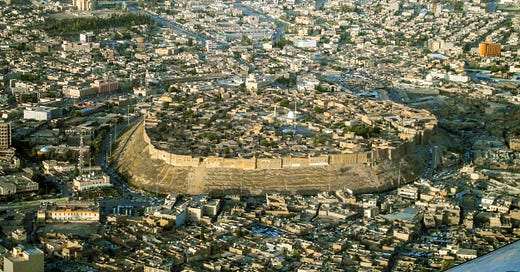

One evening, when all the delegates travelled in convoy to the Erbil Citadel, they shut down all the adjoining roads in the city with police road blocks. Whenever we drove past urban shops, everyone stopped what they were doing to come and watch us drive past as though we were royalty. It was quite something. I guess if you’re going to visit somewhere you’re not necessarily sure about, it helps to be travelling in a government car.

A Walk in the Park

I had a walk around the area the afternoon before the conference began, hoping to make it into the Sami Abdulrahman park, pictures of which looked lovely, bedecked with trees, flowers, curved walkways, and lakes. However, all the gates on our side of the city were locked and guarded by army and/or police due to the proximity to the conference hotels, so I had to walk right around the other side (in the unusually hot Iraqi sun!) to find an open gate, which seemed to take an age. I almost gave up hope after making it to several gates in a row only to find them also guarded.

Eventually, I made it inside the labyrinth. And the park gardens were indeed lovely. It made me wonder about the history of public parks as a concept. In Britain, we have the Victorians to thank for many of them, in response to the industrial revolution. Before the 1840s, aside from private country estates and occasional pleasure gardens for the rich, there basically weren’t any public parks like those we now see in our great cities. This is quite something when you think about it, not least when you realise that many of the Victorians were imbued with a Christian vision of society and culture which all too few of their great grandchildren inherited.

It’s not automatic within every culture to provide well cultivated green spaces for its people. Some have made the connection between such spaces and western peacebuilding initiatives, so I wondered how this ginormous park with lakes and rose gardens and rows of trees in a city in North-Eastern Iraq came about. It was, after all, heavily irrigated with hosepipes and taps every few metres, showing this kind of park is not quite “natural” to its desert-like habitat. It turns out this park actually used to be one of Saddam Hussein’s military bases. i.e. It was first constructed for a very different purpose, and not one that was especially friendly to Kurds! When it was converted into a park, it was later named after a former Kurdistan Deputy Prime Minister who was the victim of a suicide bombing in 2004.

The social conscience of the West may have indirectly bequeathed the idea of public parks to such regions. However, we have now largely abandoned much of our heritage, and we no longer use them the way the Victorians did. One thing I noticed in this park that we see less of in British parks today was the abundance of families having elaborate picnics, and so many children. In fact, where you do see this in British parks today, it’s usually non-native families, often Muslims, doing so.

This park also had an absurd volume of play areas, with over a hundred slides clumped together in dozens of compounds stretching over a hundred metres or so. I’ve never seen anything like it. Again, it suggests a need (and a desire) to cater for unusually large numbers of children—the kind of large families that were entirely normal in Victorian Britain (Queen Victoria herself had nine children) but is now increasingly abnormal.

This should be all the more reason for western Christians to start believing Psalm 127:5 again rather than seeing children as mere career burdens or contributors to climate change catastrophe as so many have been duped into believing, in utter revulsion of the glorious stewardly purpose portrayed in Psalm 8:6-8:

“You have made [Man] to have dominion over the works of your hands; you have set all things under his feet; all sheep and oxen, even the beasts of the field, the birds of the air and the fish of the sea that pass through the paths of the sea.”

Well cultivated public parks themselves are even a testament to godly dominion over the earth, exemplifying the “glory and honour” with which we were imbued relative to the rest of creation (Ps. 8:5) as those exclusively made in His image.

As I journeyed on through the park, I saw a boy kicking a football that found its way into my path. I passed it back to him and then I nodded for him to pass it back. Within less than a minute, a few more boys joined us and we had a goal set up and full-on match. It was a great little time. I’ve often found football a wonderful international language in this way to connect with people however little else you can understand of their language or culture. We can indeed be thankful for all good things under the sun (cf. 1Tim. 4:4) and the way we can reach out to others made in His image in and through his good gifts.

Lacking a smartphone, I had no way of “capturing” the event, but I discovered/remembered that my old phone does actually have a camera on it, albeit not an uploadable one, so you’ll have to be content with a photo of a photo…

I was invited by the various families clumped together to join them for their meal (which they had brought in various pots and pans spread out on picnic blankets) but I had to rush back to the hotel before the evening event, knowing I was probably in for a very long walk back. I asked for directions to the nearest non-military-guarded gate and went on my way.

En route, a young man in his twenties came up to me and said he had been watching our football game from afar and said he was proud to see me, an Englishman, playing with the Kurdish boys and wanted to come and shake my hand. He offered me a lift back to my hotel, which was most welcome, and offered to show me around next time I’m in the country. He was an English teacher and was very proud of Erbil and of his country, and hence proud that I was visiting it.

We in the West don’t reflect enough on this—on why we are still so respected in other parts of the world, despite often despising ourselves in our lands; on why we are glad to see other people who love their nations but castigate our own people for loving our own nations. It’s a strange, self-inflicted condition that continues to wreak untold havoc.

A “Prayer” Breakfast?

The first event of the prayer breakfast was later that evening in the Divan, where the event was held, in what I assume was certainly the most luxurious hotel in Erbil.

You had to go through security to get in and onto a very long red carpet entrance, where we were greeted by a lavish drinks reception and dinner around cabaret tables, with live music and speeches from the stage. By chance, I found myself on a table of very amiable Welshmen, who had great banter (as to be expected) despite a few theological differences, though not nearly as many as we would find with others.

What we did all agree on was the oddness that, despite this being the first meal of a weeklong “prayer breakfast” nobody at the front actually said grace before we began the meal! This, it turns out, was not a one-off. The next morning, at the first proper “breakfast” event at the same hotel, there was no grace said then, either. Nor, in fact, were there any prayers said for the entirety of the morning.

I was sat next to a Bulgarian MP at breakfast, a Christian, who saw the same oddity. After we talked about it, he messaged the next speaker, a former Slovakian Prime Minister, who replied that “in this region, this way works better, for the prayers to be embedded into the speeches”. Well, I guess this might be ok if the speeches actually did contain prayers, but they didn’t. They were mainly speeches about unity, peace, and the unique vision of Kurdistan as a tolerant place of multiple co-existent religions.

So there I was, sat there in Iraq, after an entire evening and an entire morning of a national prayer breakfast, yet to witness a single millisecond of prayer! The former Slovakian PM, prompted by my new Bulgarian friend’s message, then added a brief prayer at the end of his speech. That was something, at least, but it was still really just a prayer that the rest of the prayer breakfast would go well. I was still trying to work out what “going well” means for this kind of event. What was the ultimate purpose? It was not, after all, to pray. It was more to talk about the way that “prayer” can unite people of different beliefs.

At one point I even heard the old analogy of different religious people walking up different parts of the same mountain, finding a different path to the same God—it’s a long time since I’ve heard that one trotted out, and it was telling that it was, in light of much else that later transpired.

To be continued…

Brilliant and intensely interesting! So grateful to actually know you

Curious about the next part 🙂